Category Archives: feminism

Why Ghosting Is a Form of Self-Care

You match with someone on Tinder. Y’all text for like three days straight. Things seems to be going really well. You go on a coffee date. They seem interested and you really like them back. You lightly kiss before saying goodbye. You leave the date with the distinct impression that Things Went Well. When you get home you text them saying how good of a time you had.

No response.

You anxiously wait. Three hours go by. No response. You think they’re probably just busy, knowing something doesn’t quite feel right. Y’all kissed! They seemed interested? What changed? Was it something you said? Did they stalk your Facebook? Were you not attractive enough? Or was it your personality? A day goes by. Nothing. You text something. Still nothing. Three days later and no response.

You’ve been ghosted.

Ghosting is when someone suddenly withdraws all communication with no apparent explanation. Ghosting has now become a cultural phenomenon with the rise of online “swipe” dating apps where other real human persons are reduced to a skimpy digital profile, a mere blip in the endless stream of potential dates that you callously reject en masse on the basis of purely superficial criteria.

But is it wrong? A traditionalist might argue ghosting is wrong because you’re not being fair to the other person. They would say the right thing to do is explain why you are breaking off contact: “I don’t like you because [X].” Ghosting seems like the coward’s way out, a way of not living up to our responsibilities as dating partners. According to the traditionalist, ghosting is fundamentally a form of dishonesty.

And besides, we know that being ghosted hurts. The uncertainty is painful. I’ve been ghosted myself, of course. It doesn’t feel good, not knowing why you are being rejected. You come up with your own hypotheses about your inadequacy but you can never achieve closure. And I think it’s that lack of closure in the end that really gets you right in the gut. So we can imagine an argument that says ghosting is wrong because it hurts people.

But I am not here to criticize ghosting; I am here to defend it.

For me, ghosting is ultimately about self-care. As a woman of trans experience this is especially important to my feeling safe in dating environments. Ghosting can often feel safer rather than risking raising the ire of the person you are rejecting. While normal contexts pretending to be something you’re not is wholly virtuous, the inherent dangers of dating as a woman justify via self-defense keeping up the pretense of liking someone until the date is over and you can go home and ghost the fuck out of them, blocking them on all social media.

And if you haven’t even met in person yet, there is even more justification for ghosting as a preventative measure against the tendency of Men On the Internet not taking rejection well.

Ghosting is merely the logical conclusion of the generally accepted principle that consent can be withdrawn at anytime. Mix that in with the perfectly reasonable impulse to protect ourselves against the emotional trauma of having to reject someone (and especially of having to reject a man) and you have a good start at defending the practice of ghosting.

As someone who finds great appeal in the concept of relationship anarchy, my fundamental operating principle when it comes to relationships is to try to minimize my own entitlement. I am not entitled to other people acting the way I expect them to. I am not entitled to anyone’s attention or time. If someone consciously chooses to spend time with me, that’s great: I will cherish that. I am not entitled to people having certain kinds of feelings towards me, or entitled to having certain feelings not change over time. I am not entitled for someone to like me or even love me.

When it comes to relationships – platonic, romantic, or otherwise – the only thing I should be entitled to expect is those things which we have mutually agreed upon in accordance with our own deep desires. If my partner and I agree to be monogamous I can reasonably feel upset if that agreement is broken. But I can also negotiate a different agreement involving multiple people and that would change the nature of what I “should” expect when it comes to relationships unfolding.

And with ghosting, feeling entitled to an explanation of why you are being rejected is pointless unless you mutually agreed that if you broke up you wouldn’t ghost each other. Otherwise, you’re just going to have to deal with it. Don’t be so entitled. Learn to embrace rejection as an opportunity at character building. Know your own value and being ghosted becomes a mere inconvenience rather than a moral harm.

Filed under feminism

Ru Paul’s Drag Race Controversy: Two Trans Women Share Their Feelings

My gf Jacqueline and I share our feelings about the recent Ru Paul controversy and how it relates to the broader phenomenon of trans people, drag, and LGBTQ+ history.

Filed under feminism, Gender studies, Trans life

U-hauling, Radical Vulnerability, and the Existential Feels of Queer, Poly Love

Question: What did the lesbian bring on her second date?

Answer: A U-haul

Queer women are known for a phenomenon called “U-hauling” which is basically falling in love pretty much instantly and quickly setting in motion a Complete Entanglement, physically, financially, domestically, emotionally, etc.

In contrast, the stereotype for gay men is the tacit imposition to “not catch feels”. So why do queer women fall in love so hard and practically sprint up the relationship escalator whereas queer men tend to engage in more casual poly networks (at least according to well-known stereotypes)?

I’ve been thinking about this a lot recently because I have found myself radically in love with a girl I met…uh…three days ago? And of course the feeling is reciprocated because she is also a very gay woman and while quite new to lesbian dating is falling right in line with every stereotype. I too am a living breathing embodiment of this stereotype – especially since I just got out of a fairly serious relationship…three days ago.

I am a big advocate of thinking “coincidence” is an adequate explanation in more instances than commonly believed because the universe is often random and if you get enough people together in a room someone is bound to flip a coin heads ten times in a row. Series of relationships strung together can be just as random as starting/stopping a relationship only a few times a year.

But I have been toying with a tentative hypothesis to explain why queer women and not queer men have the stereotype of U-hauling. The story is something like this. Queer women are already on the margins of society both culturally and morally. While the tide is definitely turning there is SO MUCH hatred out there and queer women around the world get harassed and violently assaulted or even murdered on a regular basis in virtue of being queer. This process of marginalization leads to a radical vulnerability. Note: I am explicitly using “queer” and not “lesbian” because I don’t want to erase the experiences of bi/pan women.

But that’s half the equation. The other variable is the style of communication common among women. It involves deep honesty, sharing our vulnerabilities, trauma, insecurities, fears, but also our dreams and hopes and what makes us capable of still laughing in the grip of patriarchy.

As someone who has lived on both sides of the gender spectrum it is undeniable to me that there is a communication style more commonly used by women and this style facilities an openness that I think is hard for men steeped in machismo-culture to achieve. The “masc-for-masc” trend in cis gay male culture is indicative of the fact that gay men are men and in my humble opinion men and women tend to have much different communication styles.

But why is that? It’d be naive to think hormones have nothing to do with it. Most women are estrogen dominant, and again, speaking from personal experience, the emotional valences work differently and work towards facilitating a more intense resolution of conflict. Those who have lived with both Testosterone-dominance and Estrogen-dominance often report that on T they are more numb. Whether that’s a good or bad thing depends on the person. But for me the lack of numbness has led to an overall more soft and empathic response to conflict that has fundamentally changed my communication style especially in relationships

And of course, it’s not just a one-directional causality for hormones. Reductive and overly simplistic models of behavior are just that: ideal models. But socialization and learning are definitely playing a role in shaping the gender gap in communication style. But this is of course a classic chicken-and-egg question aka the old nature vs nurture chestnut. But as everyone knows the answer is both unhelpful but also the only real Truth: it is nature through nurture and nurture through nature. It is both. Interacting. In a very complex manner. Everything else is just details.

Having said that I want to turn to another cultural stereotype within the lesbian community and that is the high emphasis on monogamy culture. By that I mean emphasizing things like Soulmates, Eternal love, the One and Only, My Everything, Us vs the World, etc., etc. You can see monogamy culture working in the U-haul phenomenon because it is the sense that you suddenly have found your True Lesbian Lover that is going to satisfy all your needs until the day you die and you need to Lock That Shit Down as fast as possible otherwise it could possibly fall through your hands and you’ll die lonely and gay.

As someone who puts a high personal value on ethical nonmonogamy I am simultaneously drawn to monogamy culture and repulsed by it. I feel the temptation to use very possessive language and draw up mental entitlements to my partner’s feelings, thoughts, and behavior. But my belief in something akin to relationship anarchy makes me naturally skeptical of formal hierarchy in relationships including boundaries on what we allow ourselves to experience or not experience. Which is not to say I am against the idea of having a nesting partner(s). I am almost certainly someone who has a very strong nest-building instinct. But nesting is different from hierarchy and it is different from monogamy culture. Nesting is about mutually beneficial living arrangements but monogamy culture is about setting up toxic boundaries on our emotional openness.

And of course, I am talking about monogamy culture and not two rational and consenting adults entering into a healthy monogamous relationship which is totally possible (but maybe for less people than one might assume based on the culture we live in). Monogamy culture is toxic but monogamy itself doesn’t have to be so long as there is still radical honesty, communication, vulnerability, and empathy.

At the end of the day, U-hauling exists because queer women often spend their lives looking for something they didn’t know existed until they have their first queer relationship. As someone who has dated straight women and queer women, there is a subtle difference in virtue of relating to the shared trauma of marginalization. That background serves to make genuine connection that much more cherished and leads to the rapid emotional escalation common to lesbians and bi/pan women.

Filed under feminism, Gender studies, My life

Butterfly or Acorn? Becoming the Woman I Never Was

When a caterpillar wraps itself in its cocoon it completely dissolves into a goo. The butterfly emerges out of the goo. Is the butterfly the same entity as the caterpillar that existed pre-goo? Or is the butterfly a whole new entity? It’s easy to think of the butterfly as a new creation that sprung forth from the goo. In other words, the caterpillar didn’t turn into a butterfly, the caterpillar died and the butterfly was born anew.

In contrast, when an acorn turns into a tree it does not die. It merely grows from the inherent potential within itself. We say the acorn developed into the tree just like a child develops into an adult.

As a trans woman, I relate much more to the butterfly than I do the acorn.

Before I go on, I must insist that I am only speaking for myself. The experiences of trans people are incredibly diverse and many trans people might relate more to the acorn. The question isn’t about who’s more valid: acorns or butterflies. I believe both are valid. The right question is rather: what is your story?

The acorns of the trans world are the people who were sure of their identity from a very young age. Many of these same trans people ascribe to the “born this way” narrative where they focus strongly on genetic and biological explanations of their trans identity that places the emphasis on it being innate, a fundamental part of who they are since birth.

In contrast, I am much more of a butterfly. The way I view my journey is that I was for all intents and purposes a man prior to transition. I performed the social role well and this performance did not conflict with my identity. I was, however, a gender nonconforming male who had a feminine side I had been exploring from a young age. I played with this juxtaposition for many years until my marriage ended in my late twenties and an opportunity for further gender exploration opened up.

The more I explored my femininity the more I realized desires were emerging that told me I could no longer live a dual life. I needed to make a binary transition into womanhood. This was largely the result of living in a society that makes it very difficult for a male-identified person to make a complete social/physical/presentational transition while still holding onto their male identity.

Like it or not we live in a binarist culture where manhood and womanhood are associated with certain stereotypes. I began to realize that I wanted nothing to do with manhood and the toxic masculinity endemic to our patriarchal culture.

Hormone therapy activated emotional circuits that allowed me to feel empathy in a way that I previously was unable to.

Social transition provided an opportunity to learn about systemic oppression and taught me solidarity with folks of all stripes. My eyes were opened up to how fucked up this world is and how oppression really functions in this society.

My loss of male privilege gave me new a new epistemic and moral perspective from which to analyze the world. Direct exposure to rampant transphobia gave me insight into the power structures that are actively working to maintain white supremacy, cissexism, ableism, patriarchy, etc.

Transition made me aware of what it’s like to fear walking down the street by yourself. It taught me to fear men. In so many ways transition has changed my entire political/social worldview. I went from being one of the most privileged people on this planet to someone who can now understand what solidarity really means.

But transition also was the catalyst for my metaphormophis. Transition turned my male identity into a goo out of which emerged a woman exploring her identity.

I relate to the butterfly instead of the acorn because I don’t like to focus on the innate factors that predisposed me to explore femininity in the first place. I prefer instead to focus on the interpersonal-social-environmental-learning-cultural-reflective-introspective factors that led to the breakdown of my male identity and provided the matrix through which my trans identity developed.

I worry that the “born this way” narrative is dangerous fodder for conservatives and TERFs hellbent on trans genocide. If we find a biological cause of trans identity, would some parents screen and terminate their babies if they thought they’d turn out trans? After all, many people see it as a medical condition or disorder of some kind. Whether its a psychiatric disorder or endocrinological disorder doesn’t matter – if it’s a disorder why wouldn’t people try to eradicate it from our species?

This is one of the reasons why I prefer to focused on the non-biological factors at play in the formation of my trans identity. Obviously there was some biological factors at play because it’s always a mixture both nature and nurture. But in so many trans narratives we see a reluctance to talk about the non-biological factors. There is a fear that if we admit such factors people will either think we’re phonies or that we can just go to therapy to cure ourselves of the desire to transition.

I reject both claims. Just because there are non-biological factors at play does not entail that conversion therapy will work. The presence of non-biological factors does not mean that we can just consciously choose to be trans. The question of “is it a choice” is over simplified because we have to distinguish between unconscious and conscious cognitive processes. The unconscious feeds off many non-biological factors same as the conscious system. The existence of choice does not mean that it’s willy-nilly and can just be consciously overridden.

Furthermore, nobody is born with a “doctor gene”. But obviously if you choose to be a doctor that doesn’t make you a phony doctor. Similarly, there is probably not a single “trans gene”. But choosing to become a woman doesn’t make you a phony woman. It’s the performance of doctorhood that makes you a doctor and for me it’s the performance of womanhood that counts. Moreover, “performing womanhood” is not the same as performining femininity. You can violate every stereotype known and still perform womanhood authentically.

And once you perform a role long enough it becomes automatized, habitualized, unconscious, and thus “natural”. It becomes part of the unconscious schemas that structure your total personality.

While in many ways I am still quite similar to the man I once was, in many more ways I am a new person. Going on the classic Lockean model of personal identity, there are enough significant psychological discontinuities with who I once was to warrant thinking I am a whole new person.

I have become the woman I never was.

I was decidedly not a woman born into the body of a man but rather a man who turned into a woman. I was not a woman peering out from behind the eyes of a male. I was a gender nonconforming male who had a complex set of new desires emerge from a period of gender exploration in my twenties. This desires included a desire for a feminine name, she/her pronouns, hormone therapy, laser treatment, and a complete change in appearance.

My sexual desires also changed. I went from being bi-curious to pansexual.

All my feelings about my body changed. I did not have significant body dysphoria before transition. Transition precipitated most of my gender dysphoria. It was not gender dysphoria that caused transition but transition that caused the dysphoria.

Again, I want to emphasize this might not be true of all trans people. We all have our own stories, our own life history, and what’s true for me is might not be true for anyone else.

But I think we do a disservice to ourselves by focusing too many on acorns while ignoring butterflies. Both are beautiful. Both are valid.

Filed under feminism, Gender studies, My life, Trans studies

Trans Feminism Is Real Feminism

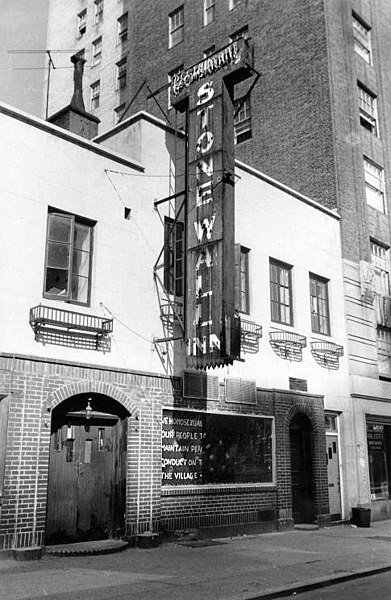

Marsha “P” Johnson – Civil rights activist who famously started the Stonewall Riots which led to the modern LGBT+ rights movement

Trans feminism sometimes gets mistaken as feminism’s little cousin, a mere side show to the Main Event: Cis Feminism i.e. feminism written by and for other cis women.

On a superficial level, this seems fitting. After all 99% of women on this planet are cis so it makes sense that “feminism” is largely concerned with the perspective of cis women. According to this logic, “trans feminism” is merely “feminism light”, a pale shadow of the real thing.

But I want to argue that not only is trans feminism real feminism, real feminism *must* incorporate the insights of trans feminism if it is to be complete, to the extent any feminism can ever be complete.

Intersectional feminism is basically the idea that if you are a black woman the oppression you face as a black woman intersects with the oppression you face as a black woman. Gender and race also intersect with socio-economic status, disability, orientation, etc.

Being trans is just another axis along which intersectionality functions. Any feminism worth its weight recognizes this. Trans women have experiences that overlap with cis women as well as experiences that don’t. But that’s not inherently different than black women having experiences that overlap/don’t overlap with white women.

In my opinion it’s a fool game to try and find the experience or set of experiences that is universal among all women. But that doesn’t entail the concept “woman” is without meaning. Philosophers have noted it’s surprisingly difficult to give necessary and sufficient conditions for simple concepts like “chair” – yet I know a chair when I see one.

Why should we expect complex concepts like “woman” are any different? I might not be able to define womanhood precisely in such a way that will correctly sort billions of unique individuals into two mutually exclusive classes: women and not-women. It’s not so easy! Yet I know a woman when I see one. And “seeing” here is of course a metaphor for understanding. A pre-transition trans woman can radiate her womanhood without necessarily “passing” as a woman. “Passing” as a cis woman is such an arbitrary standard anyway because there are cis women who get misgendered on a regular basis.

Why will feminism never be complete without the inclusion of trans people? Because feminism has inputs. It’s not just done completely a priori. It operates with experiences and narratives as data to be explained. Traditional feminism started with only the experiences of white middle-class women as the inputs and got quite a bit done. But it was far from complete. Then black feminists started feeding in their inputs. And through similar processes the voices of people from diverse backgrounds have given their inputs.

Trans people represent 1% of the population. That might not sounds like a lot but that’s millions and millions of data points. And furthermore, they are data points that are highly relevant to feminism insofar as trans people have unique insights into the dynamics of gender, which should be of special interest to feminist theory. So not only does trans feminism bring the experience of millions of trans women, trans men, and non-binary folks, it brings it in such a way that has the potential to reshape the very concepts central to feminism.

Some prominent feminist theorists such as Judith Butler have recognized this conceptual potential and have started to work through those insights. And of course trans feminists themselves have been dissecting this stuff for decades.

But feminism has yet to fully digest the trans experience. Though a mere “1%” trans folks have so much to bring to feminism, with spectacular proclivity to keep pressuring feminism to remain intersectional.

A common phenomenon in intersectional feminism is a feminism that believes itself to be fully intersectional yet is missing the perspective of important class(es) of people. To me it seems the best tactic is to remain humble about the intersectional reach of our feminism. There are probably voices feminism has yet to hear, stories that are important for understanding the full operation of intersectional semiotics.

Any feminism without trans experience is partially blind. This is why trans feminism is real feminism. Real feminism is spongelike in its absorption of different perspectives. Any feminism that fails to uptake the experience of trans people is incomplete at best and actively harmful at worst.

Filed under feminism, Trans studies

On Being an Angry Tranny

I am an angry tranny.

Yes, tranny. Not trans woman. Because when both liberals and conservatives see a trans woman getting upset over some social justice issue they are not thinking “Oh those angry trans women”. They’re thinking to themselves “Fucking trannies always getting their panties in a twist.”

The “angry tranny” archetype was made famous in the Stonewall riot, where trans women threw the first bricks kicking off the historical fight for LGBT rights which is now a major social movement.

(Source: wikipedia commons)

Trans women, especially trans women of color, have been behind every major civil rights issue since forever. They are the original agitators. They agitate simply in virtue of existing. The refusal to obey the rules assigned to them by a cissexist patriarchical society agitates the inner gears of the gender machine, the all encompassing system of norms, uwritten rules, scripts, stereotypes, etc. that defines our existence in a human society and feeds off all human difference.

Trans women, especially trans women of color, have very good reasons to be pissed off at all kinds of fucked up shit in our society with all its destructive systems of oppression, discrimination, exploitation, corruption, prejudice, violence, and marginalization.

And it’s not just gender. The whole system is corrupt – capitalism doesn’t escape the ire of the angry tranny.

I wasn’t always this angry. Transition slowly changed how I viewed the world. It changed my internal moral life and gave me the perspective to understand the concept of solidarity with folks living in oppressive systems. I went from literally being one the most privileged people on the planet to someone with a whole lot more to lose by remaining silent about social injustice.

(source)

I can no longer afford to be cordial, intellectual, rarified, theoretical in my direct discourse. As an ex-academic philosopher I spent a lot of time hanging out with white cis straight males who have a tendency to treat reality like a thought experiment. They debate social issues like an intellectual debate, a game of wit and logical acumen.

The question for me used to be “Who has the most clever argument?” but now my instinct leans towards “Who is this hurting?”

It’s funny how being a target of harassment, violence, hate and governmental regulation concerning what I do with my body will make you a more stringent feminist.

So many white cis people use the stereotype of the angry tranny, of the angry feminist, the angry WOC, to invalidate our experiences, our analysis, our solutions.

But until all systems of oppression are eradicated, I will remain angry, agitated, and antagonistic.

There Is Nothing Universal to Say About Trans Women and Male Privilege

There has been a lot of ink spilled lately about trans women and male privilege. I have seen so many discussions recently where people ask the question “Do trans women as a whole have male privilege and if so what kind and how much?” And then you see some trans women writing articles responding to this drivel by arguing “That doesn’t match my experience” and then go on to detail how their lives were not filled with privilege and how in fact they were brutalized for being feminine as children and did not internalize society’s messages about male socialization the same way cis boys did.

And on the other hand, some trans women are writing articles saying “I did have male privilege but I gave it up or am in the process of giving it up oh and btw I’m still a woman” or something along those lines. I’ve seen some of these articles also make the general claim that some types of male privilege were afforded to ALL trans women in virtue of living a life pre-transition as someone who was coded as male. But then other trans women deny this reflects their own experience growing up and we are going in a circle, with universal claims being negated by individuals claims and individual claims being taken as proof of some universal claim.

This is tiresome.

We have a general claim about ALL trans women being refuted by individual claims about SOME trans women. But the trans women who did not experiences themselves as having male privilege often make the same mistake of thinking their experience is universal. That’s what so wrong with this whole discussion. There are no universals. There are no generalizations to be made in terms of ALL trans women – every trans woman has a difference experience of living pre-transition as well as experiences their loss of privilege via transition differently.

And furthermore, people like to frame the discussion in terms of the pointless question of whether trans women’s experiences are identical to cis women’s experiences. But who cares? It doesn’t matter. Our experiences don’t need to perfectly match the cis experience to be representative of womanhood because to think otherwise is to buy into the cis-sexist belief that the cis experience is the “default” and the trans experience is a pale imitation. But in reality the trans experience is equally valid, it’s just more rare.

Personally, my own experience pre-transition featured a good deal of male privilege which I’ve wrote about elsewhere . I’ve retained some vestiges of that male privilege such as the privilege having grown up not thinking of myself as an emotional creature but rather a rational creature. I still have the privilege of not worrying about getting pregnant. But much of the other privileges I gave up during transition or am in the process of giving up. I now fear walking down the street at night whereas before I never did. I now fear cat-calling – before it was not even on my mind. I’ve lost the privilege of not worrying about my drink being drugged at a bar. I’ve lost the privilege of not fearing men. The list goes on.

The point is that privilege is rarely so monolithic or one-dimensional. My privilege as a white person and the vestigial remains of my male privilege is balanced against my loss of privilege as a woman and especially as a trans woman.

But my experience says nothing about the experiences of other trans women, who experienced their gender much differently than I did as a child and as I do now. I was never really made fun of for being feminine – my feminine behaviors were done in secret behind closed doors and so they weren’t a target for harassment. I was able to regiment my personality into a public boyish self and a private feminine self. It’s a myth that gender identity is formed for life within the first 5 years of life. While that might be true for many people it is not a universal truth. My gender identity has evolved significantly since I was 5 years old and I know I am not alone though I have the feeling that many trans people have a bias towards interpreting their memories as having an earlier identity because that narrative is seen as “more valid” than the ones where gender identity evolution occurs later in life.

Not all young trans girls are able to hide their natural femininity and they are brutalized for it. If someone went through that experience and they are telling you they did not have male privilege then I believe it’s epistemically best practice to head what they are saying and take their narrative seriously. Likewise if a trans woman says she used to have male privilege but has since given most of it up, we need to listen to that narrative as well.

Cishet people seem to be more convinced that if a trait is displayed earlier in life it is “more natural” and thus a product of someone’s core essence. But that’s the wrong question to be asking. Innate or not, natural or not, what we should care about is if a behavior, trait, or personality is authentic and representative of someone’s deepest vision for how they want their life to go, regardless of the “origins” of that vision. If someone’s trans identity originated in their 40’s that does not make their trans identity less authentic than someone who’s trans identity originated in childhood. If someone starts painting in their 40s does that make them “less” of a painter than someone who has been painting since infancy? A painter is someone who paints. A trans person is someone with a gender identity different from their assigned gender. It’s not “gender identity different from assigned gender but also having emerged by five years old”. It just has to be different. But the causal origins of the identity itself in terms of when it originated in the life-line are not relevant for determining the authenticity of of the identity.

My trans identity only surfaced in my late 20s. It would be SO easy and no one could prove me wrong if I began saying things like: “I felt off during puberty but I only learned the words to articulate my feelings years later”. In a sense that would be perfectly true. I did have gender issues at a young age. But I think I would be deluding myself if I claimed I had any awareness of ever wanting to transition at that age. Just like gender identity doesn’t have to be cemented in childhood, neither does dysphoria have to originate in childhood. Dysphoria can surface at any point in a trans person’s life. I didn’t start feeling real dysphoria until my late 20s. The longer we hold onto the traditional narrative that all trans people somehow “knew” then they were children, the longer we will be unable to see the true diversity of the trans community.

The problem comes when we try to generate a one-size-fits-all theoretical framework for thinking about ALL trans women as sharing some kind of universal essence. But that’s a pipedream. There is no universal narrative. The human mind strives to “connect the dots” and create some kind of overarching generalization that is true of all trans women. But we need to resist that and instead focus on studying individual differences.

Filed under feminism, Gender studies, Trans studies

(Photo by

(Photo by  (pixabay)

(pixabay) (Photo by

(Photo by

(Photo by

(Photo by  (pixabay)

(pixabay)